Is AI a Repeat of the Dot-Com Bubble of 2000?

The immense amount of investment being poured into AI is an undisputed fact, companies and investors are piling billions into the ecosystem, driving valuations to unseen heights. Comparisons between today’s artificial intelligence boom and the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s are becoming increasingly common. Some commentators even claim the US economy is hinging on this bubble and is bound to crash when it pops. In both cases, we see the rise of a transformative technology, a rapid surge in company valuations, and soaring expectations. However, simple similarities can sometimes be misleading. Are the parallels indeed so evident? Why are professional investment funds still riding this train?

This is our take on whether the comparison is fully justified and why we would argue that today’s AI surge is built in many respects on more solid foundations than the speculative enthusiasm that surrounded the early internet bubble. Below we suggest 5 factors that can perhaps add more nuance to the picture of today’s AI boom and how it differs from the dot-com bubble:

- Strong revenues and profits among some leading AI companies.

During the dot-com bubble, the majority of internet startups were unprofitable, only around 14% were making money at the peak of the boom. Today, the leading companies driving AI development are generating real revenues and profits. Technology giants involved in AI, such as NVIDIA, Meta, Microsoft, and Google, have long been highly profitable enterprises and can afford the insane levels of investment AI demands. This fundamental difference shows that the current AI boom is not based solely on promises, but on businesses with solid financial foundations. Of course there are also many examples to the contrary, but the trend is far from one-sided. - More rational market valuations.

In 2000, valuations of internet companies reached extreme levels, disconnected from their fundamentals. For example, the Nasdaq-100 tech index had a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 60 in March 2000. In contrast, as of October 2025, the P/E ratio for the Nasdaq-100 stands at 35,13, so just over half of what it was during the dot-com peak. Today, shares of the largest AI-related companies are priced far more reasonably, reflecting strong earnings growth rather than pure speculation about the future. Again, this is not universally true, but is far from what we saw 20 years ago. - Widespread adoption of AI technology.

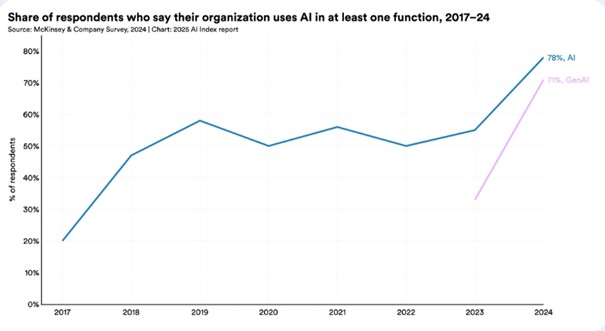

Artificial intelligence is already in broad use, proving its real-world utility. According to a 2024 McKinsey report, between 70% and 78% of companies worldwide are using some form of AI. Billions of people interact with AI systems daily from voice assistants in smartphones to content recommendations on websites. By comparison, around the year 2000, the internet had only about 361 million users globally, just 6% of the world’s population. This means the dot-com bubble was built on a much smaller user base, whereas today’s AI boom addresses a truly global audience. While there may be some tough times ahead of some AI companies and sectors as the inflated expectations crash into economic reality (see MIT study on ROI), but we feel in the long term AI has a strong economic basis.

- Investment in infrastructure.

The current AI boom is supported by unprecedented investment in tangible resources, which was lacking on such a scale during the dot-com era. Companies are spending massive sums on data centers, semiconductor chips, and the cloud infrastructure required to power AI systems. Global investment in AI is projected to reach $5 trillion by 2030. Governments also play a much greater role in funding AI development. In contrast, many 1990s dot-com companies operated on shaky external financing models that quickly collapsed when investor sentiment shifted. It’s true that some of this may look like circular investments and seem too inflated to be reasonable, but overall brick and mortat investment is a more stable game than valuations based on promises and delusions of grandeur. - Real applications and economic value.

Artificial intelligence is already delivering tangible benefits across many industries, boosting productivity and creating new services. Projections suggest that AI could add nearly USD 15.7 trillion to global GDP, unlocking unprecedented productivity gains and accelerating innovation across sectors. AI not only inflates company valuations but also generates real economic growth, unlike during the dot-com bubble, when many companies operated without real added value and without any idea of how to convert popularity into sustainable income. At that time, firms were often judged by web traffic alone, rather than profitability or meaningful innovation. It’s estimated that about 40% of dot-com companies were highly overvalued and ultimately failed once investors began demanding actual financial results.

Does this mean we’ll avoid a crash like the one that followed the dot-com bubble? No one can predict the future and certainly some concerns are not unwarranted. Every period of rapid growth carries the risk of corrections, overinvestment, or shifts in market sentiment. The AI sector is not immune to these dynamics. Today’s boom appears to rest on stronger foundations such as real revenues, widespread adoption, and substantial infrastructure investment. This doesn’t eliminate risk, but it suggests we’re dealing with a more mature and economically grounded trend than we saw during the dot-com era.